Mayor of Ankara

In office

10 December 1973 – 12 December 1977

Preceded by Ekrem Barlas

Succeeded by Ali Dinçer

Personal details

Born 10 November 1927

Elazığ, Turkey

Died 21 March 1991 (aged 63)

Kırıkkale, Turkey

Nationality Turkish

Political party Republican People's Party

Alma mater Istanbul Technical University

Occupation Architect, politician

Vedat Ali Dalokay (November 10, 1927 – March 21, 1991) was a renowned Turkish architect and a former mayor of Ankara.

Early life

He was born in Elazığ, Turkey from kurdish family in 1927 to İbrahim Bey from Pertek.[1] He completed his elementary and secondary education in the same city. Then he left for Istanbul for a university degree and graduated from the Faculty of Architecture of Istanbul Technical University in 1949. Later in 1952, he completed his post-graduate studies at the Institute of Urbanism and Urban Development of Sorbonne University in Paris, France.

Career

Along with numerous national award-winning projects in Turkey, Dalokay has been awarded internationally for the Islamic Development Bank (1981) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and perhaps his most famous project, the Faisal Mosque (1969) in Islamabad, Pakistan.

His design for the Kocatepe Mosque in the Turkish capital, Ankara was selected in the architectural competition but, as a result of controversial criticism, was not built. Later, a modified design was used as a basis for the Faisal Mosque in Islamabad.

His design for the Kocatepe Mosque in the Turkish capital, Ankara was selected in the architectural competition but, as a result of controversial criticism, was not built. Later, a modified design was used as a basis for the Faisal Mosque in Islamabad.

In 1973, he was elected the Mayor of Ankara from the CHP. Dalokay had served until the 1977 local elections, when another CHP member, Ali Dinçer was elected to replace him.

Death

Vedat Dalokay died in a traffic accident on March 21, 1991, in which his wife Ayça (age 44) and son Barış (age 17) were also killed.

-wiki

Faisal Masjid in Islamabad, Pakistan was designed by Vedat Dalokay

Faisal Masjid at night around prayers time

Naz, Neelum. METU JFA 2005/2 (22:2) - Contribution of Turkish Architects to the National Architecture of Pakistan: Vedat Dalokay PDF (885 KiB)

Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı - The Kocatepe Mosque Complex 1967-1987, Ankara PDF (6.03 MiB)

Drawings and model photos of Vedat Dalokay's unbuilt mosque design for the Kocatepe Mosque

Animation of Vedat Dalokay's unbuilt mosque design for the Kocatepe Mosque

As, Imdat, "Vedat Dalokay's Unbuilt Project: A Lost Opportunity," in "The Digital Mosque: A New Paradigm in Mosque Design" Journal of Architectural Education (JAE), Volume 60, Issue 1, 2006, pp.54-66

As, Imdat "The Kocatepe Mosque Experience, " in Emergent Design: Rethinking Contemporary Mosque Architecture in Light of Digital Technology, S.M.Arch.S. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 2002. pp.24-46

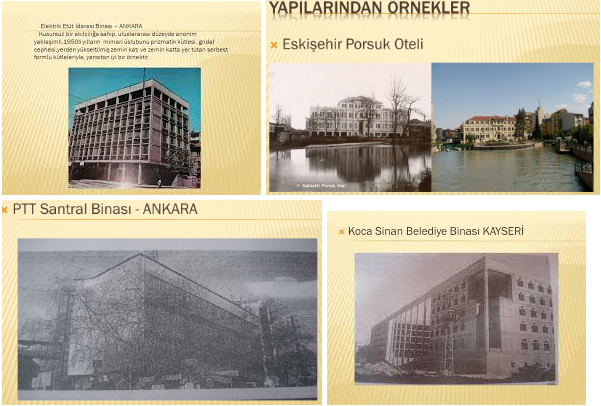

his works:

Vedat Dalokay, and his Turkish heritage.

Neelam Naz, Professor in Architectural Department, University of the

Engineering and Technology, Lahore, writes in a research paper that Vedat Dalokay was

born in Elazig, Turkey November, 1927. After completing his elementary and secondary

education in Elazig, he joined the Technical University of Istanbul to study architecture.

Upon completing his degree in 1949 he received the title “Yukesek Muhandis Mimar”.

Then he worked for the Ministry of Works and National Post Telephone Telegraph

Department for a short period. In 1950 he left for France and entered the City Planning

Department at the Sorbonne in Paris. In the same year he registered for Ph.D. studies, but

later left that program.1

In 1952, he completed his post-graduate studies at the Institute

of Urbanism and Urban Development of the Sorbonne University in Paris, France.2

Naz

mentions that in 1954 he established an office in Ankara. In 1980 he won the award from

“Turk Dil Kuumu” (the Institute of Turkish Language) for his story book written for

children titled “Kolo”. He became the President of the Chamber of Architects in Ankara,

144

in 1964-1968. He was Mayor of Ankara in 1973-1977. He died in March 21, 1991 in a

tragic car accident at the age of sixty four.3

Prior to the commission for the Faisal Mosque Dalokay had won forty national

and six international competitions. The most renown of these and the one which first

brought him recognition beyond Turkey was his awarded for the Islamic Development

Bank in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1981 (plate 222).4

In Pakistan, before the Faisal Mosque,

he designed two buildings, a Islamic Summit Minar, Lahore, 1977 (plate 224) and the

Prime Ministry Complex, Islamabad, 1986 (plate 225).

Naz mentions a list of twenty two buildings designed by Vedat Dalokay. Only

three of them are outside of Turkey, the Islamic Development Bank, Riyadh, Saudi

Arabia, 1981, the Prime Ministry Complex, Islamabad, Pakistan, 1986 and the Faisal

Mosque, Islamabad, 1988.

His architectural projects in Turkey, as listed by Neelam Naz, and others in the

order in which they were built or commissioned are: Conversion of Mecka Army

Barracks to Army Museum, 1951; building of General Directorate for Electrical works,

(1955), Porsuk Hotel, Eskisehir (1956); civil servants fund multi-story building, Kizilay

(1956); provincial cooperative residences (1956); a bus station, Eskisehir (1956); the

Government Mansion, Bitlis (1957); Kocatepe Mosque, Ankara (1957); Konya College,

Konya (1957); PTT Exchange Building, Cebeci, Ankara (1958); Central building of

Institute of Turkish Standards (TSE) and Laboratories (1960); Atomic Research Center,

Ankara (1961), Child Care Center, Ankara (1961); plan for bank sea Technical

University (KTU) campus, Trabzon (1962); Central Bank Branch, Kayseri (1964);

technical school, Ege University, 1964; Social Security Institute Hospital, Elazig (1965);

Sekerbank Gerneral Directorate Building (1968); Child Care Center, Adana (1968);

Women Teachers College, Zonguldak (1968) Medical Faculty of Black Sea University

(1972); and plan for the Taksim Square, Istanbul (1987) are Dalokay’s national winning

projects.5

145

For the design of Kocatepe Mosque, Ankara, a competition was held in Ankara in

1957. Among thirty-six entries the joint project of Vedat Dalokay and Nejat Tekelioglu

was nominated as the best one. The foundation for it was laid in 1963.6

Vedat Dalokey

had proposed a concrete shell dome structure with four pointed minarets. But because of

heavy criticism for its modernist look, the construction was stopped at the foundation

level (plate 226-227).7

Later the design of another architect of Turkey was selected for

the Kocatepe Mosque. The design, however, was not a modern one but in Ottoman

architectural style resembling with Blue Mosque in Istanbul.8

Above the square sanctuary of the Kocatepe Mosque, Dalokay proposed a huge

dome with soft and curvilinear lines. The semi-circular roof joined from its corners with

the bases of the four minarets. The structure under the canopy had rectangular walls and

rectangular linear designs on its surface.

Dalokay later used a modified design of the Kocatepe Mosque for the Faisal

Mosque, Islamabad: the original domed structure was changed for a modern one. It was

adopted with the back ground of the Faisal Mosque. The mosque is designed in accord

with the diagonal lines of the Margala hills. The sanctuary of the Faisal Mosque is square

in plan, four triangular walls, roof with eight triangular slabs has sharp contours, finial

with crescent and sharp stylization in its expression. The walls of the Kocatepe Mosque

are quite different from the constructive designs of the triangular walls of the Faisal

Mosque.

The architect designed four stylized minarets at the corner of the sanctuary for

both mosques. Minarets of both mosques are similar in their square tall shaft and pointed

tops. But the bases are different from each other. The bases of the Kocatepe Mosque’s

minarets are square in plan with chamfered corners are in short proportion to the overall

height. But the bases of the Faisal Mosque’s minarets are square, tapered and much

taller. The overall impression of the Faisal Mosques minarets is rocket like. These two

146

mosques are Dalokay most famous projects and are known and popular to a large

audience. They are his only religious buildings.

In 1977, Vedat Dalokay designed the Islamic Summit Minar located on the

Upper Mall Road in front of the Punjab Assembly Hall in Lahore. The Minar is designed

with square base, shaft and top, made of white marble. The corners of the Minar are in

concave form and the four sides are vertically recessed at the centers. Resemble with the

square piers made of poured concrete in the covered area before the rectangular open

court on the ground floor at the Faisal Mosque. The center third of each side of the pier

of the covered area in the Faisal Mosque is recessed but its recessed area is broader then

the recessed part of the Islamic Summit Minar (plate 31, 224). On the Islamic Summit

Minar the joining of every marble slab makes prominent horizontal and vertical lines

visible from a distance. The piers of the covered area in the Faisal Mosque have further

divisions into horizontal units too. The square top of the Islamic Summit Minar has deep

curves from four sides but the top of the Faisal Mosque’s minarets is pointed (plate 10).

Allah-u-Akbar is written on four sides of the square base in stylized Kūfic (plate 223).

The top ending of the calligraphic words are similar with the top of the name of Allah

written on the mihrāb in the Faisal Mosque (plate 116). The twisted forms on the hastae

“replace” the knots on the Kūfic on the walls of the staircases in the ablution area.

Overall design of the Minar is totally different from the minarets of the Faisal Mosque.

The Minar stands in the middle of a recessed courtyard. The round arches for an arcade

in front of a public library.

The Faisal Mosque is his most famous project. The mosque project was signed in

1969 but only completed nineteen years late, in 1988. The building is designed according

to latest scientific technology, techniques and materials. Dalokay believed that an

architectural monument was a landmark and point of identity of a society. It should have

its planned functions, be technically sound, and convey an aesthetic meaning.9

The

design of the Faisal Mosque fulfills these qualities.

147

In the years after the construction of the Faisal Mosque, several architects of

Pakistan were inspired by its unique exterior. These “replicas” show the importance and

popularity of the Faisal Mosque. We have found several mosques in the Punjab province

of Pakistan that adopt features of the Faisal Mosque, including the use of monumental

Kūfic calligraphy, the design of the entrance doors of the sanctuary, the coffered ceilings

of the covered area after the main entrance of the ground floor and western staircases in

the ablution area, the pyramidal roofing of the exterior of the sanctuary, and the tall slim

minarets. Several of the mosques inspired by Dalokay’s exteriors will be introduced

below.

The Jami‘ Mosque of the Defence Housing Authority (Phase I) in Lahore, built in

1988, has an entrance area with bold pseudo-Kūfic calligraphy in relief form on the

exterior walls (plate 228). Like modified the Kūfic calligraphy of the west wall in the

Faisal Mosque in tile mosaic, the exterior entrance wall of the Defence Mosque has

calligraphy in relief form that is stylized and bold. The relief work of the Kūfic

calligraphy on the mihrāb in the sanctuary of the Faisal Mosque has flat and sharp cuts

with gold colour on white Thassos marble. Comparatively, the relief of the Defence

Mosque is made of concrete and cement in two levels and painted in light green against a

white back ground.

In the Defence Mosque the courtyard is surrounded by porticos on the east, north,

and south sides with large semicircular intersecting vaults that rest on square poured

concrete piers (plates 229). The lower part of the pier is decorated with white ceramic

tiles with a floral decorative band of quatrefoils in blue and white. The upper cement

surface is painted green with white (plate 230).

For the entrance doors of the sanctuary clear glass is fitted in black aluminum

frame (plate 231) and have similarities with the sanctuary doors of the Faisal Mosque

(plate 68). The sanctuary is rectangular in plan, without any vertical support. The

coffered ceiling (plate 232) is inspired by the coffered ceiling of the covered area of the

148

ground floor and the western staircases in the ablution area of the Faisal Mosque (plates

31, 39).

Several recent examples of pyramidal roof in the Punjab have been found that

have not been previously mentioned in any book or on any web site: the Jami‘ Mosque,

Raiwind Road, Lahore, built in 1999 (plate 233); the Masjid-i-Burhan, Gullberg, Lahore,

built in 1999 (plate 234); the Kalar Kahar Mosque, on M-2 near Motor Way, built in

1999 (plate 235) and the Jami‘ Mosque, Faisalabad, built in 2000 (plate 236). Their

sanctuaries are constructed on a square plan and crowned by pyramidal roofs. Their roofs

dominate the structure in busy sections of cities. The pyramidal roof construction of

these mosques is based on continuity of strict sharp geometry that gives a bold

impression at the Faisal Mosque. Comparatively, only their sharpness and sloping lines

from their cardinal point of the roof are close to the Faisal Mosques roof structure.

The Shaukat Khanam Hospital Mosque, Lahore, built in 1994 has an unusual

design that is not depended on the usual prototype forms of dome and arches. The

architect tried to employ new concepts of modernity. Its roof is composed of six threedimensional

equilateral triangles in constructive form or pyramids (plate 237). The

eastern entrance doors of the sanctuary, like those of the main entrance of the Faisal

Mosque, are tinted glass in black aluminum frame (plate 238). The tile decoration with

octagonal stars and arabesques on the entrance pillars of the sanctuary (plate 239) has a

traditional appearance. Its octagonal star shape is found in the Faisal Mosque on the

octagonal star of the lattice work of the women’s gallery. (plate 92).

The Jami‘ Masjid Shuhda-al-hadith, Balakot, built in 2000, is a perfect example

of use of the pyramidal roof in the northern areas of Pakistan. It was completely

destroyed during an earthquake on October 8, 2005 (plate 240).

The Bilal Masjid, Shahpur, Sargodha, built in 1993 (plate 241), and the Mari

Mosque of Sargodha, built in 2000 (plate 242) are good examples of pitched roof

construction in modern mosque design and are directly influenced by the roof design of

149

the Faisal Mosque. They have pyramidal and gable roofs with four minarets. But here

these replicas of the Faisal Mosque are built on the corners of a square plan sanctuary.

Two elements of the Faisal Mosque’s sanctuary are present. The local architects tried to

build small replicas of the Faisal Mosque but the quality is poor: they are unfinished and

imperfect in construction. Their minarets, built on the four corners of the roof, are too

small in size, and the buildings are on cramped lots. The use of pitched roofs, rather that

the traditional dome, highlights the importance of their model, the Faisal Mosque.

The slender and sharply pointed minarets of the Faisal Mosque also provide a

model for later mosques of the Punjab. Pointed tops with crescents on the four minarets

of the Jami‘ Mosque, Raiwind Road, Lahore, built in 1999 are influenced by the Faisal

Mosque’s minarets (plate 236). Minarets with pointed tops are found at Lal Masjid,

Islamabad, built in 1989 (plate 244) and the ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque (also called the Data

Darbar), Lahore, begun July 2, 1981 and completed November 28, 1989 (plate 245).10

However, the minaret of the ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque is round and rest on square base; the

round shafts and pointed top following the structural type of typical Ottoman minarets.

The Faisal Mosque, with its pointed top is on a square base, breaks from the normal

Ottoman minaret style.

The round and pencil point ‘Turkish” minaret of the ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque,

Lahore, are placed on a square base, and as in the Faisal Mosque, they are deeply

embedded (sixteen feet) below ground level. The minaret base is decorated with cerulean

and cobalt blue tile mosaic work. The shaft of the minaret is painted white with two

balconies of blue paint. The tips of the pencil point tops of the minaret are made of

stainless steel and covered with gold leafing.11

The sanctuary of the ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque is rectangular and has arch-shape

roofing rather than a traditional dome. The sanctuary is built without any vertical

support. The women’s galleries rest on massive square piers, with the side pillars

150

forming equilateral arches and have carved wood, lattice work, and inlayed tile mosaic

work. Kūfic calligraphy is preferably adopted for decoration of the Ka’bah wall (plate

246).

The ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque shows the best adaptation of the architectural

innovations introduced at the Faisal Mosque: the open interior of the mosque without

supportive pillars, the square bases for the minarets and its pencil point apexes. But these

architectural elements do not an exact copy those of the Faisal Mosque, and more

importantly, the aesthetic values and elements of art of the original structure are totally

changed.

The Islamic Development Bank in Jeddah, Saudi

Notes

1

Neelam Naz, “Contribution of Turkish Architects to the National Architecture of Pakistan: Vedat

Dalokay”, Metujfa 22:2 (Feb 2005), 51.

2

http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-5316/2005/cilt22/sayi_2/51-

77.pdf%20page%2053%20to%2055, (accessed Nov 29, 2007).

3

Naz, “Contribution of Turkish Architects to the National Architecture of Pakistan: Vedat Dalokay”, 55.

4

http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-5316/2005/cilt22/sayi_2/51-

77.pdf%20page%2053%20to%2055, (accessed Nov 29, 2007).

5

Naz, “Contribution of Turkish Architects, 55; http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-

5316/2005/cill22/sayi_2/51-77.pdf (accessed May 15, 2007).

6

Ismail Serageldin and James Steele, Architecture of the Contemporary Mosque (London: Academy

Group, 1996), 109.

7

http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-5316/2005/cill22/sayi_2/51-77.pdf (accessed May 15, 2007);

Serageldin and Steele, Architecture of the Contemporary Mosque, 102.

8

Brochure by the Turkish Ministry of Religious Affairs, “Ankara Kocatepe Camii 1967-1987”;

http://www.diyanetvakfi.org.tr/eserler/kocatepecamii/kocatepe_camii.pdf (accessed May 6, 2008);

9

Interview with Ahmad Rafiq civil engineer of the Faisal Mosque, July 14, 2004.

10 Gafer Shehzad, Data Darbar Complex (Lahore: Adrak Publication, 2004), 54-55, (in Urdu).

11 Shehzad, Data Darbar Complex, 70.

http://slideplayer.biz.tr/slide/2318684/

http://documents.tips/documents/mimar-vedat-ali-dalokay.html

Drawings and model photos of Vedat Dalokay's unbuilt mosque design for the Kocatepe Mosque

Animation of Vedat Dalokay's unbuilt mosque design for the Kocatepe Mosque

As, Imdat, "Vedat Dalokay's Unbuilt Project: A Lost Opportunity," in "The Digital Mosque: A New Paradigm in Mosque Design" Journal of Architectural Education (JAE), Volume 60, Issue 1, 2006, pp.54-66

As, Imdat "The Kocatepe Mosque Experience, " in Emergent Design: Rethinking Contemporary Mosque Architecture in Light of Digital Technology, S.M.Arch.S. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 2002. pp.24-46

his works:

Vedat Dalokay, and his Turkish heritage.

Neelam Naz, Professor in Architectural Department, University of the

Engineering and Technology, Lahore, writes in a research paper that Vedat Dalokay was

born in Elazig, Turkey November, 1927. After completing his elementary and secondary

education in Elazig, he joined the Technical University of Istanbul to study architecture.

Upon completing his degree in 1949 he received the title “Yukesek Muhandis Mimar”.

Then he worked for the Ministry of Works and National Post Telephone Telegraph

Department for a short period. In 1950 he left for France and entered the City Planning

Department at the Sorbonne in Paris. In the same year he registered for Ph.D. studies, but

later left that program.1

In 1952, he completed his post-graduate studies at the Institute

of Urbanism and Urban Development of the Sorbonne University in Paris, France.2

Naz

mentions that in 1954 he established an office in Ankara. In 1980 he won the award from

“Turk Dil Kuumu” (the Institute of Turkish Language) for his story book written for

children titled “Kolo”. He became the President of the Chamber of Architects in Ankara,

144

in 1964-1968. He was Mayor of Ankara in 1973-1977. He died in March 21, 1991 in a

tragic car accident at the age of sixty four.3

Prior to the commission for the Faisal Mosque Dalokay had won forty national

and six international competitions. The most renown of these and the one which first

brought him recognition beyond Turkey was his awarded for the Islamic Development

Bank in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1981 (plate 222).4

In Pakistan, before the Faisal Mosque,

he designed two buildings, a Islamic Summit Minar, Lahore, 1977 (plate 224) and the

Prime Ministry Complex, Islamabad, 1986 (plate 225).

Naz mentions a list of twenty two buildings designed by Vedat Dalokay. Only

three of them are outside of Turkey, the Islamic Development Bank, Riyadh, Saudi

Arabia, 1981, the Prime Ministry Complex, Islamabad, Pakistan, 1986 and the Faisal

Mosque, Islamabad, 1988.

His architectural projects in Turkey, as listed by Neelam Naz, and others in the

order in which they were built or commissioned are: Conversion of Mecka Army

Barracks to Army Museum, 1951; building of General Directorate for Electrical works,

(1955), Porsuk Hotel, Eskisehir (1956); civil servants fund multi-story building, Kizilay

(1956); provincial cooperative residences (1956); a bus station, Eskisehir (1956); the

Government Mansion, Bitlis (1957); Kocatepe Mosque, Ankara (1957); Konya College,

Konya (1957); PTT Exchange Building, Cebeci, Ankara (1958); Central building of

Institute of Turkish Standards (TSE) and Laboratories (1960); Atomic Research Center,

Ankara (1961), Child Care Center, Ankara (1961); plan for bank sea Technical

University (KTU) campus, Trabzon (1962); Central Bank Branch, Kayseri (1964);

technical school, Ege University, 1964; Social Security Institute Hospital, Elazig (1965);

Sekerbank Gerneral Directorate Building (1968); Child Care Center, Adana (1968);

Women Teachers College, Zonguldak (1968) Medical Faculty of Black Sea University

(1972); and plan for the Taksim Square, Istanbul (1987) are Dalokay’s national winning

projects.5

145

For the design of Kocatepe Mosque, Ankara, a competition was held in Ankara in

1957. Among thirty-six entries the joint project of Vedat Dalokay and Nejat Tekelioglu

was nominated as the best one. The foundation for it was laid in 1963.6

Vedat Dalokey

had proposed a concrete shell dome structure with four pointed minarets. But because of

heavy criticism for its modernist look, the construction was stopped at the foundation

level (plate 226-227).7

Later the design of another architect of Turkey was selected for

the Kocatepe Mosque. The design, however, was not a modern one but in Ottoman

architectural style resembling with Blue Mosque in Istanbul.8

Above the square sanctuary of the Kocatepe Mosque, Dalokay proposed a huge

dome with soft and curvilinear lines. The semi-circular roof joined from its corners with

the bases of the four minarets. The structure under the canopy had rectangular walls and

rectangular linear designs on its surface.

Dalokay later used a modified design of the Kocatepe Mosque for the Faisal

Mosque, Islamabad: the original domed structure was changed for a modern one. It was

adopted with the back ground of the Faisal Mosque. The mosque is designed in accord

with the diagonal lines of the Margala hills. The sanctuary of the Faisal Mosque is square

in plan, four triangular walls, roof with eight triangular slabs has sharp contours, finial

with crescent and sharp stylization in its expression. The walls of the Kocatepe Mosque

are quite different from the constructive designs of the triangular walls of the Faisal

Mosque.

The architect designed four stylized minarets at the corner of the sanctuary for

both mosques. Minarets of both mosques are similar in their square tall shaft and pointed

tops. But the bases are different from each other. The bases of the Kocatepe Mosque’s

minarets are square in plan with chamfered corners are in short proportion to the overall

height. But the bases of the Faisal Mosque’s minarets are square, tapered and much

taller. The overall impression of the Faisal Mosques minarets is rocket like. These two

146

mosques are Dalokay most famous projects and are known and popular to a large

audience. They are his only religious buildings.

In 1977, Vedat Dalokay designed the Islamic Summit Minar located on the

Upper Mall Road in front of the Punjab Assembly Hall in Lahore. The Minar is designed

with square base, shaft and top, made of white marble. The corners of the Minar are in

concave form and the four sides are vertically recessed at the centers. Resemble with the

square piers made of poured concrete in the covered area before the rectangular open

court on the ground floor at the Faisal Mosque. The center third of each side of the pier

of the covered area in the Faisal Mosque is recessed but its recessed area is broader then

the recessed part of the Islamic Summit Minar (plate 31, 224). On the Islamic Summit

Minar the joining of every marble slab makes prominent horizontal and vertical lines

visible from a distance. The piers of the covered area in the Faisal Mosque have further

divisions into horizontal units too. The square top of the Islamic Summit Minar has deep

curves from four sides but the top of the Faisal Mosque’s minarets is pointed (plate 10).

Allah-u-Akbar is written on four sides of the square base in stylized Kūfic (plate 223).

The top ending of the calligraphic words are similar with the top of the name of Allah

written on the mihrāb in the Faisal Mosque (plate 116). The twisted forms on the hastae

“replace” the knots on the Kūfic on the walls of the staircases in the ablution area.

Overall design of the Minar is totally different from the minarets of the Faisal Mosque.

The Minar stands in the middle of a recessed courtyard. The round arches for an arcade

in front of a public library.

The Faisal Mosque is his most famous project. The mosque project was signed in

1969 but only completed nineteen years late, in 1988. The building is designed according

to latest scientific technology, techniques and materials. Dalokay believed that an

architectural monument was a landmark and point of identity of a society. It should have

its planned functions, be technically sound, and convey an aesthetic meaning.9

The

design of the Faisal Mosque fulfills these qualities.

147

In the years after the construction of the Faisal Mosque, several architects of

Pakistan were inspired by its unique exterior. These “replicas” show the importance and

popularity of the Faisal Mosque. We have found several mosques in the Punjab province

of Pakistan that adopt features of the Faisal Mosque, including the use of monumental

Kūfic calligraphy, the design of the entrance doors of the sanctuary, the coffered ceilings

of the covered area after the main entrance of the ground floor and western staircases in

the ablution area, the pyramidal roofing of the exterior of the sanctuary, and the tall slim

minarets. Several of the mosques inspired by Dalokay’s exteriors will be introduced

below.

The Jami‘ Mosque of the Defence Housing Authority (Phase I) in Lahore, built in

1988, has an entrance area with bold pseudo-Kūfic calligraphy in relief form on the

exterior walls (plate 228). Like modified the Kūfic calligraphy of the west wall in the

Faisal Mosque in tile mosaic, the exterior entrance wall of the Defence Mosque has

calligraphy in relief form that is stylized and bold. The relief work of the Kūfic

calligraphy on the mihrāb in the sanctuary of the Faisal Mosque has flat and sharp cuts

with gold colour on white Thassos marble. Comparatively, the relief of the Defence

Mosque is made of concrete and cement in two levels and painted in light green against a

white back ground.

In the Defence Mosque the courtyard is surrounded by porticos on the east, north,

and south sides with large semicircular intersecting vaults that rest on square poured

concrete piers (plates 229). The lower part of the pier is decorated with white ceramic

tiles with a floral decorative band of quatrefoils in blue and white. The upper cement

surface is painted green with white (plate 230).

For the entrance doors of the sanctuary clear glass is fitted in black aluminum

frame (plate 231) and have similarities with the sanctuary doors of the Faisal Mosque

(plate 68). The sanctuary is rectangular in plan, without any vertical support. The

coffered ceiling (plate 232) is inspired by the coffered ceiling of the covered area of the

148

ground floor and the western staircases in the ablution area of the Faisal Mosque (plates

31, 39).

Several recent examples of pyramidal roof in the Punjab have been found that

have not been previously mentioned in any book or on any web site: the Jami‘ Mosque,

Raiwind Road, Lahore, built in 1999 (plate 233); the Masjid-i-Burhan, Gullberg, Lahore,

built in 1999 (plate 234); the Kalar Kahar Mosque, on M-2 near Motor Way, built in

1999 (plate 235) and the Jami‘ Mosque, Faisalabad, built in 2000 (plate 236). Their

sanctuaries are constructed on a square plan and crowned by pyramidal roofs. Their roofs

dominate the structure in busy sections of cities. The pyramidal roof construction of

these mosques is based on continuity of strict sharp geometry that gives a bold

impression at the Faisal Mosque. Comparatively, only their sharpness and sloping lines

from their cardinal point of the roof are close to the Faisal Mosques roof structure.

The Shaukat Khanam Hospital Mosque, Lahore, built in 1994 has an unusual

design that is not depended on the usual prototype forms of dome and arches. The

architect tried to employ new concepts of modernity. Its roof is composed of six threedimensional

equilateral triangles in constructive form or pyramids (plate 237). The

eastern entrance doors of the sanctuary, like those of the main entrance of the Faisal

Mosque, are tinted glass in black aluminum frame (plate 238). The tile decoration with

octagonal stars and arabesques on the entrance pillars of the sanctuary (plate 239) has a

traditional appearance. Its octagonal star shape is found in the Faisal Mosque on the

octagonal star of the lattice work of the women’s gallery. (plate 92).

The Jami‘ Masjid Shuhda-al-hadith, Balakot, built in 2000, is a perfect example

of use of the pyramidal roof in the northern areas of Pakistan. It was completely

destroyed during an earthquake on October 8, 2005 (plate 240).

The Bilal Masjid, Shahpur, Sargodha, built in 1993 (plate 241), and the Mari

Mosque of Sargodha, built in 2000 (plate 242) are good examples of pitched roof

construction in modern mosque design and are directly influenced by the roof design of

149

the Faisal Mosque. They have pyramidal and gable roofs with four minarets. But here

these replicas of the Faisal Mosque are built on the corners of a square plan sanctuary.

Two elements of the Faisal Mosque’s sanctuary are present. The local architects tried to

build small replicas of the Faisal Mosque but the quality is poor: they are unfinished and

imperfect in construction. Their minarets, built on the four corners of the roof, are too

small in size, and the buildings are on cramped lots. The use of pitched roofs, rather that

the traditional dome, highlights the importance of their model, the Faisal Mosque.

The slender and sharply pointed minarets of the Faisal Mosque also provide a

model for later mosques of the Punjab. Pointed tops with crescents on the four minarets

of the Jami‘ Mosque, Raiwind Road, Lahore, built in 1999 are influenced by the Faisal

Mosque’s minarets (plate 236). Minarets with pointed tops are found at Lal Masjid,

Islamabad, built in 1989 (plate 244) and the ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque (also called the Data

Darbar), Lahore, begun July 2, 1981 and completed November 28, 1989 (plate 245).10

However, the minaret of the ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque is round and rest on square base; the

round shafts and pointed top following the structural type of typical Ottoman minarets.

The Faisal Mosque, with its pointed top is on a square base, breaks from the normal

Ottoman minaret style.

The round and pencil point ‘Turkish” minaret of the ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque,

Lahore, are placed on a square base, and as in the Faisal Mosque, they are deeply

embedded (sixteen feet) below ground level. The minaret base is decorated with cerulean

and cobalt blue tile mosaic work. The shaft of the minaret is painted white with two

balconies of blue paint. The tips of the pencil point tops of the minaret are made of

stainless steel and covered with gold leafing.11

The sanctuary of the ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque is rectangular and has arch-shape

roofing rather than a traditional dome. The sanctuary is built without any vertical

support. The women’s galleries rest on massive square piers, with the side pillars

150

forming equilateral arches and have carved wood, lattice work, and inlayed tile mosaic

work. Kūfic calligraphy is preferably adopted for decoration of the Ka’bah wall (plate

246).

The ‘Ali Hajvairy Mosque shows the best adaptation of the architectural

innovations introduced at the Faisal Mosque: the open interior of the mosque without

supportive pillars, the square bases for the minarets and its pencil point apexes. But these

architectural elements do not an exact copy those of the Faisal Mosque, and more

importantly, the aesthetic values and elements of art of the original structure are totally

changed.

The Islamic Development Bank in Jeddah, Saudi

Notes

1

Neelam Naz, “Contribution of Turkish Architects to the National Architecture of Pakistan: Vedat

Dalokay”, Metujfa 22:2 (Feb 2005), 51.

2

http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-5316/2005/cilt22/sayi_2/51-

77.pdf%20page%2053%20to%2055, (accessed Nov 29, 2007).

3

Naz, “Contribution of Turkish Architects to the National Architecture of Pakistan: Vedat Dalokay”, 55.

4

http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-5316/2005/cilt22/sayi_2/51-

77.pdf%20page%2053%20to%2055, (accessed Nov 29, 2007).

5

Naz, “Contribution of Turkish Architects, 55; http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-

5316/2005/cill22/sayi_2/51-77.pdf (accessed May 15, 2007).

6

Ismail Serageldin and James Steele, Architecture of the Contemporary Mosque (London: Academy

Group, 1996), 109.

7

http://jfa.arch.metu.edu.tr/archive/0258-5316/2005/cill22/sayi_2/51-77.pdf (accessed May 15, 2007);

Serageldin and Steele, Architecture of the Contemporary Mosque, 102.

8

Brochure by the Turkish Ministry of Religious Affairs, “Ankara Kocatepe Camii 1967-1987”;

http://www.diyanetvakfi.org.tr/eserler/kocatepecamii/kocatepe_camii.pdf (accessed May 6, 2008);

9

Interview with Ahmad Rafiq civil engineer of the Faisal Mosque, July 14, 2004.

10 Gafer Shehzad, Data Darbar Complex (Lahore: Adrak Publication, 2004), 54-55, (in Urdu).

11 Shehzad, Data Darbar Complex, 70.

http://slideplayer.biz.tr/slide/2318684/

http://documents.tips/documents/mimar-vedat-ali-dalokay.html

The Islamic Development Bank in Jeddah, Saudi

Vedat Dalokay Parkı

VEDAT DALOKAY WEDDING HALL HAS BEEN RENOVATING

Taksim Meydanı

[PDF]THE ARCHITECT: “VEDAT DALOKAY” AS A SOCIAL AGENT A ...

https://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12610349/index.pdf

by B SUZAN - 2008 - Related articles

Dec 29, 2008 - Keywords: Architect, Identity, Social Agency, Social Transformation, Vedat ... Bu çalışma mimar Vedat Dalokay' ın toplumsal bir aktör olarak ...